Article: What’s the most important non-technical skill you look for in an engineer?

Imagine you’ve been tasked with hiring an engineer who can possess only one of the following skills: communication, critical thinking, or adaptability.

Which skill would you look for? Which do you think will matter most in a future where AI will transform an increasing percentage of our technical engineering workload?

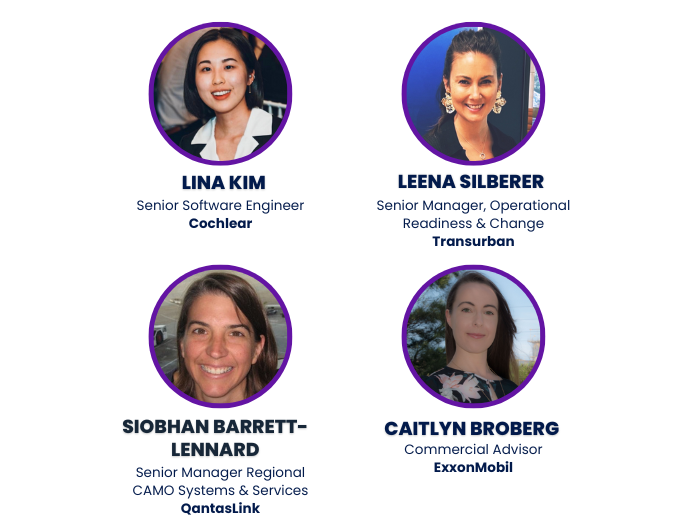

We asked these questions and several more in an interview with four thought-leaders speaking at the upcoming Women in Engineering Summit 2025. Read on to discover insights from Lina Kim (Senior Software Engineer, Cochlear), Leena Silberer (Senior Manager, Operational Readiness & Change, Transurban), Siobhan Barrett-Lennard (Senior Manager Regional CAMO Systems & Services, QantasLink), and Caitlyn Broberg (Commercial Advisor at ExxonMobil).

How do you believe technical skills complement non-technical skills in your engineering work?

According to Kim, technical skills are essential for analysing and implementing solutions – they answer the “how,” while non-technical skills help uncover the right problem to solve and align the people involved, addressing the “what” and “who.”

“It’s crucial to recognise that spending a lot of time on the wrong problem is not the best use of an engineer’s time,” Kim says. “In projects with multiple team members, identifying the right skills for the right problem becomes critical. This is where non-technical skills, such as clear communication and diligence, come into play.”

Kim shares an example of this in practice: “In a recent project involving a cross-functional system with a mobile team, Cloud team, and IT department, we faced an issue during a system launch. No one person could possibly have had all the context, so we needed open and clear communication and a shared vocabulary to connect the dots. This was essential for determining whether the issue needed escalation and how quickly, which tied into time management, resource allocation, and ultimately, project delivery.”

Barrett-Lennard believes non-technical skills complement technical skills by helping with personal relationships, which builds team cohesiveness. “To solve a problem, it generally takes collaboration and communication, so these skills go hand in hand with problem-solving and technical skills to find a solution,” she adds.

Broberg added her perspective, saying, “Both technical and non-technical skills are extremely important in my current role as a Commercial Advisor, as well as in all my previous process engineering roles. Technical skills like process simulation and data analysis have allowed me to find new ways to optimise complex systems, but without non-technical skills such as communication, teamwork, and adaptability, these ideas would never have been implemented.”

A specific example of where strong communication skills enhanced her ability to solve a technical problem happened when Broberg was troubleshooting a production issue at site. By practicing active listening and curiosity while working closely with operations field personnel, her team was able to discover an innovative solution to a problem that had not been seen through technical modelling alone.

In Silberer’s opinion, there are several non-technical skills that come into play when solving any problem. “Firstly, to properly understand the problem, context is everything,” she says. “That could mean using your existing relationships to hear perspectives from various stakeholders, building new, positive relationships in order to extract good quality information and background, and using empathy and active listening to know what to ask and to whom, and when to listen.”

“Secondly,” she continues, “in order for an effective solution to be designed and implemented, it needs to be well understood by those delivering it, requiring good communication, and accepted by the end user, requiring an understanding of the needs of the stakeholders and purpose. For example, taking the time to ask the right questions to an end user may surface a need for a design that focuses on high maintainability, rather than the lowest cost.”

What strategies do you use to hone your technical and non-technical skills, and how do you prioritise which skills to focus on?

“Most of my non-technical skills training has come from watching my peers and leaders in how they work, as well as reading articles about leadership and teamwork,” says Barrett-Lennard. “My company provides continuous learning opportunities by sharing leadership tips and links to relevant articles. Generally, one-on-ones with my manager and six-monthly performance reviews are great times to discuss which skills, both technical and non-technical, need development and the best ways to approach that.”

Broberg believes experience and learning on the job is the fastest way to develop both technical and non-technical skills. “On-the-job learning works best when complemented by effective and targeted formal training courses, as well as strong mentoring and coaching programs,” she notes. “For me, prioritising the development of technical versus non-technical skills depends on the role I am in and where my greatest skill gaps are at the time. For example, when I took on my first leadership assignment, I focused mainly on building my non-technical leadership and people management skills, whereas in my current role, I am focusing a lot more on developing my technical knowledge of commercial and energy markets.”

Silberer has found a mix of formal training and on-the-job learning to be the best way to hone her skills. “Mentoring helps to inspire and unlock new ways to learn, but it doesn’t go as deep as an experience at work, such as when we make a mistake and learn from it. Both of my degrees, civil engineering and an executive MBA, felt at times to be futile, crammed with theory I thought I wouldn’t ever use. But as I progress in my career, I realise that it isn’t useful until you find a purpose for it and use it often. One of the most powerful skills I have learnt is effective leadership, and that has been my priority. Whether managing a team, a project, a disparate group of stakeholders, or managing up, leadership is about understanding the value that everyone brings to the table and experimenting with ways to unlock that both in an individual and a team.”

Kim shares her strategies: “I actively seek opportunities to mentor juniors. There’s a saying that one of the most effective ways to learn something is by teaching others, known as the protégé effect. I volunteer to mentor graduates and interns and to speak at tech expos, conferences, and knowledge-sharing meetups. I also attend cross-disciplinary conferences, workshops, or hackathons to not only hone my technical skills but also to connect with others in the industry. I participate in events like Engineers in Australia, university events, and networking sessions, and I keep an eye out for lectures on interesting topics, particularly in my core area of interest, which is IT in healthcare.”

“Additionally,” continues Kim, “I seek feedback not just from my manager but also from stakeholders I regularly interact with regarding my project management skills, leadership, communication, and presentations. I’ve found great value in simply asking, ‘Which skill do you think I should focus on?’ This provides me with valuable insights from multiple perspectives. I prioritise my development based on current gaps and recent feedback.”

Do you believe there are ANY technical skills that are safe from being replaced by AI? What non-technical skills do you think engineers will need to cultivate to remain effective in their roles?

Broberg notes that there are still technical engineering skills that are safe from being replaced by AI (particularly narrow AI). Examples include field engineering and troubleshooting, which generally require contextual awareness, real-time decision making, and physical interaction with unpredictable systems. “However,” she adds, “as applications for AI continue to expand and develop beyond narrow AI, my advice for engineers is to strengthen their strategic thinking, communication skills, and experience with real-world systems, plant, and operating equipment to remain effective in their roles.”

Silberer agrees that apart from physical technical skills, it seems unlikely that many skills are safe. But non-technical skills are another matter: “In large, complicated, and complex projects – especially those with a large number of stakeholders – communication, empathy, a growth mindset, and the ability to prioritise effectively are essential non-technical skills unlikely to be effectively performed by AI.”

Kim tells us that personally, she’s very excited about what AI will bring and enable in the future. “It’s daunting to think about job market prospects, but at the same time, I trust that we will be more prepared than we think. We should remember that it’s going to be a process rather than an overnight loss of millions of jobs. We have time to prepare, adjust, re-train, and shift. Often the elements of fear stem from the assumption that change will be immediate and absolute rather than gradual and navigable.”

Kim continues: “The key skills I see are systems thinking and architecture design, which require the ability to make contextual judgements. This means understanding and considering complex, interdependent systems, making trade-offs that reflect long-term vision, team dynamics, allocated resources, timelines, business goals, industry standards, market conditions, and risks. AI lacks the domain context, business constraints, and ethical foresight necessary for these decisions.”

Kim adds that ethical engineering and consideration of human factors are crucial, as decisions that involve social impact, accessibility, and ethical trade-offs require empathy. “Non-technical skills to cultivate include soft skills such as negotiation, conflict resolution, and leadership within a team – especially for engineers in leadership positions. Adaptability is critical; we need to stay technically curious and not feel threatened by AI. We fear what we do not understand, so we must continue to use, experiment, and leverage AI.”

Technical Skills that deal with exceptions are an area that AI will struggle with, notes Barrett-Lennard. “AI builds from data/experience/research that already exists, but there are always exceptions. On the human side, intuition and cultivating personal relationships will always be critical non-technical skills.”

If you had to hire someone who possessed only one of the following non-technical skills (Adaptability, Communication, Critical Thinking), which would you choose?

“For me, it would always be communication," says Silberer. “If we are able to communicate well, those other skills can be taught. It’s important to recognise that non-technical skills can be learned in any stage of life and are not reserved for this born with them, or for extroverted individuals. If we have a learning mindset; if we are aware of and are okay with our limitations and open to change, we can start to question the way we have always done things and find a way to grow.”

Provided she was hiring an engineer, Kim would choose critical thinking. “In an engineering project, critical thinking enables us to identify the right problem to solve and determine the best approach given multiple limitations. It allows engineers to question assumptions, test boundaries, analyse root causes, and make sound judgements after considering all factors. I believe a strong critical thinker can learn to communicate better and adapt faster, but the reverse isn’t always true. While adaptability and communication are essential skills for becoming a successful team member, I also believe that critical thinking is a multiplier for both technical performance and team outcomes, especially in complex engineering projects, as critical thinkers can identify blind spots that others may miss.”

For Barrett-Lennard, adaptability is a critical non-technical skill: “Everyone in an organisation thinks and works slightly differently and may come from different perspectives. Being able to adapt the way we communicate, adjust how we explain concepts, and modify solutions for particular changing scenarios is key.”

Broberg notes that all three skills are important, and the answer may depend on the role and nature of the work environment. “For example, adaptability is key in fast-paced, constantly changing work environments like plant operations, and communication is essential where there are many cross-functional and/or external interfaces, such as client-facing roles. However, if I had to pick one, I would say critical thinking is the most important of these skills. It sets the foundation for problem-solving, which is fundamental to any engineer’s success. It also helps people prioritise and use clear and logical reasoning to ensure sound judgment under pressure, providing the basis from which to develop communication and adaptability.”

Want to learn more?

Join Caitlyn Broberg, Siobhan Barrett-Lennard, Lina Kim, Leena Silberer, and dozens of other industry thought-leaders at the Women in Engineering Summit 2025, to be held at Pullman Sydney Hyde Park, 14 – 16 October.

Download the Brochure